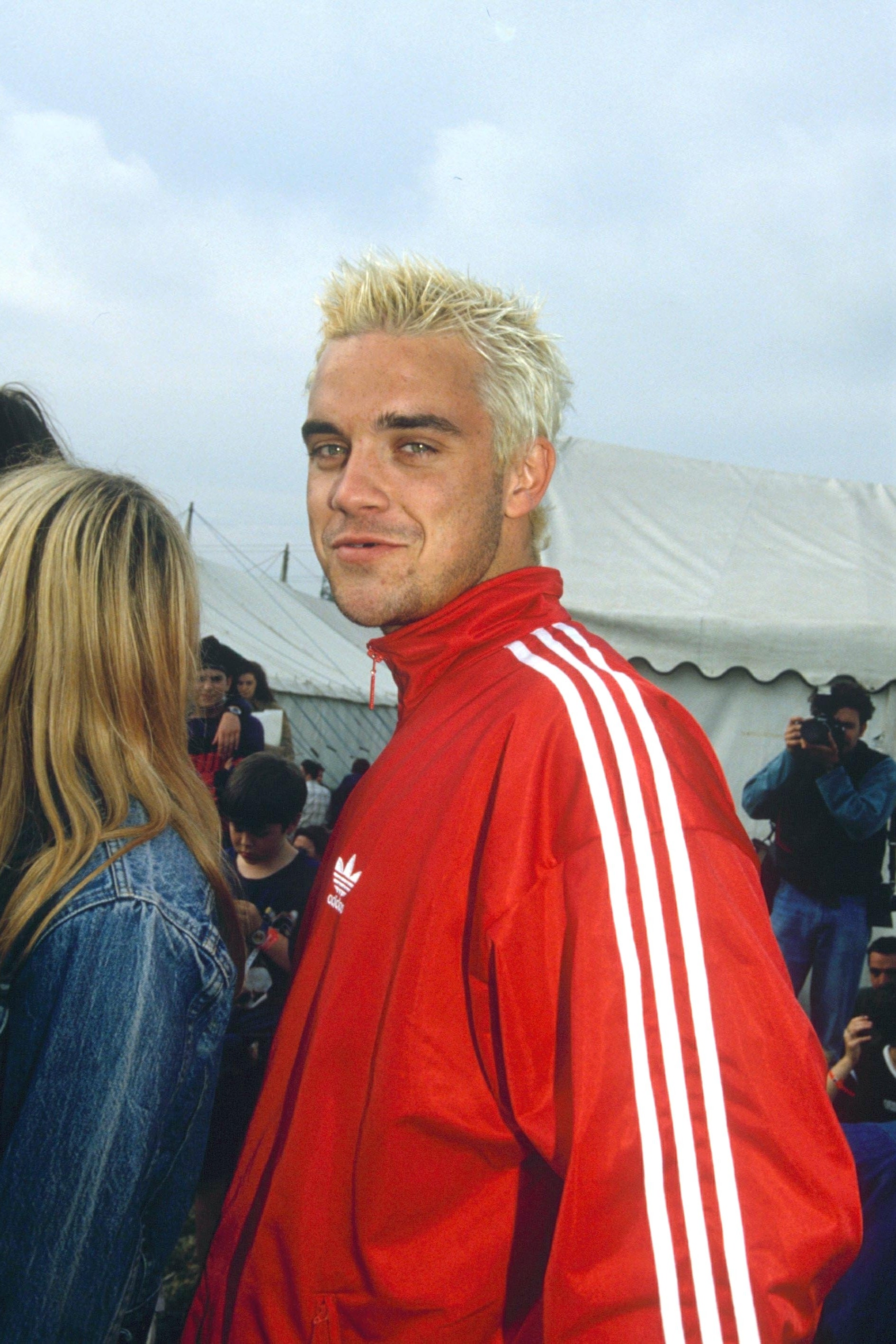

When the Robbie Williams biopic Better Man came out at the end of last year, director Michael Gracey (The Greatest Showman, Rocketman) held out hopes that the chimpanzee musical might resonate with US audiences. “It’s truly exciting that they’re hearing these songs for the first time in the film,” he told IndieWire, referring to the fact that – despite selling over 75 million records worldwide – most Americans still don’t know who Williams is.

Gracey shouldn’t have held his breath. Americans don’t “get” Robbie Williams now, just like they didn’t in 1999, back when he signed to Capitol Records and embarked on a tour across North America. After Better Man, the disgruntled TikToks started rolling in from across the pond. “We don’t like him,” said one user. “The music is not good and the music ya’ll keep playing to tell us that he’s good… we don’t like it.” For others, they thought his lack of American fame must equate to not being famous globally. “Every so often somebody tries to convince me that there’s a person who’s been around all along and I can’t help but feel like I’m being gaslit,” said another. “This… Robbie Williams?”

Predictably, Brits flipped out en masse (British culture is dunking on Britain constantly until an American does it and then suddenly you’re the most patriotic person on earth). Indeed, there’s a particular type of deranged British vs American head-butting online that starts with a person in, say, Arizona asking something innocuous like “what’s baked beans?” and ends with someone in Kent frothing at the mouth and rage-typing “AT LEAST WE DON’T HAVE GUNS!!” To that end, the Robbie Williams back and forth should have come as no surprise. What is surprising, however, is the idea that Americans ever should or would get Robbie Williams, Mr Rock DJ, our Robbie from Stoke-on-Trent, to begin with.

At the centre of all of this confusion, it seems, is his music, which doesn’t always translate for reasons that are complicated and hard to explain. Robbie has never been an incredible singer (he can belt; you can tell he was raised on pub cabaret). He’s had a number of misses in among his myriad hits (someone hide “Rudebox” from the American people). His songs, which have often teetered between bolshiness and fragility, ego and vulnerability, Britpop and showtunes-esque balladry, don’t really make sense without the man himself. Because to try and understand Robbie based on his music alone is to miss the point entirely. It’s like judging a Wetherspoons meal on its actual taste, rather than the ritual of getting a full English for £5.75 on a hangover. Or trying to explain why smoking areas are culturally significant. They just are. Robbie Williams just is. And we love him for it.

Robbie doesn’t tone down his British-isms, but instead leads with them, because he can’t help it. In a 2011 interview with Vogue, he said the sentence “Slags are what I like” (try to imagine, like, Bruno Mars saying that). His song “Angels” has become such a mainstay among the pubs and clubs of Britain that there is not a single person who would need the lyrics in order to sing it at karaoke. When he played Knebworth in 2003, marking the biggest music event in UK history, he said, “You’ve watched me grow up so far. I wanna get old with you lot. Please, please don’t leave me.” He is charm and bravado personified, but – unlike a more poised and shiny American swag or earnestness – there’s a fragility simmering just beneath the surface, with a heavy dose of winking sarcasm on top of that. He sang it himself in “Come Undone”: “So ‘need your love’, so ‘fuck you all’.”

Some Brits might tell you that they love Robbie Williams ironically, but they’d be lying. There’s a widespread affection for Robbie over here – and, oddly, among the rest of the world bar America – that isn’t dissimilar to the affection one might feel for their hometown or first love. He makes you want to roll your eyes and get misty-eyed at the same time. The opening chords to “Let Me Entertain You” is like knocking back a tequila shot after work on a Friday. Whether or not he “makes sense” in America – ever did, ever needs to – is irrelevant. As Moya Lothian-McLean put it in Line of Best Fit: “Robbie was never going to make it there. He has too much about him. Coldplay could crack the US with bland, inoffensive stadium rock, but Robbie, with his demons and his tattoos and his hedonism? Absolutely not, and it’s their loss.”

Robbie knows that America doesn’t get him. He jokes about it all the time. When an American interviewer recently asked him if there was anything he wanted to say to his “fans in America” who might be experiencing his story for the first time, he turned straight to the camera, the hint of a smile on his lips. “Yeah I’ll speak to that one fan. Hi Linda! You alright? Nice to see you. Sorry I haven’t been back to America since the last century but it’s nice that you still check out my stuff online. How are the family, are they good?”